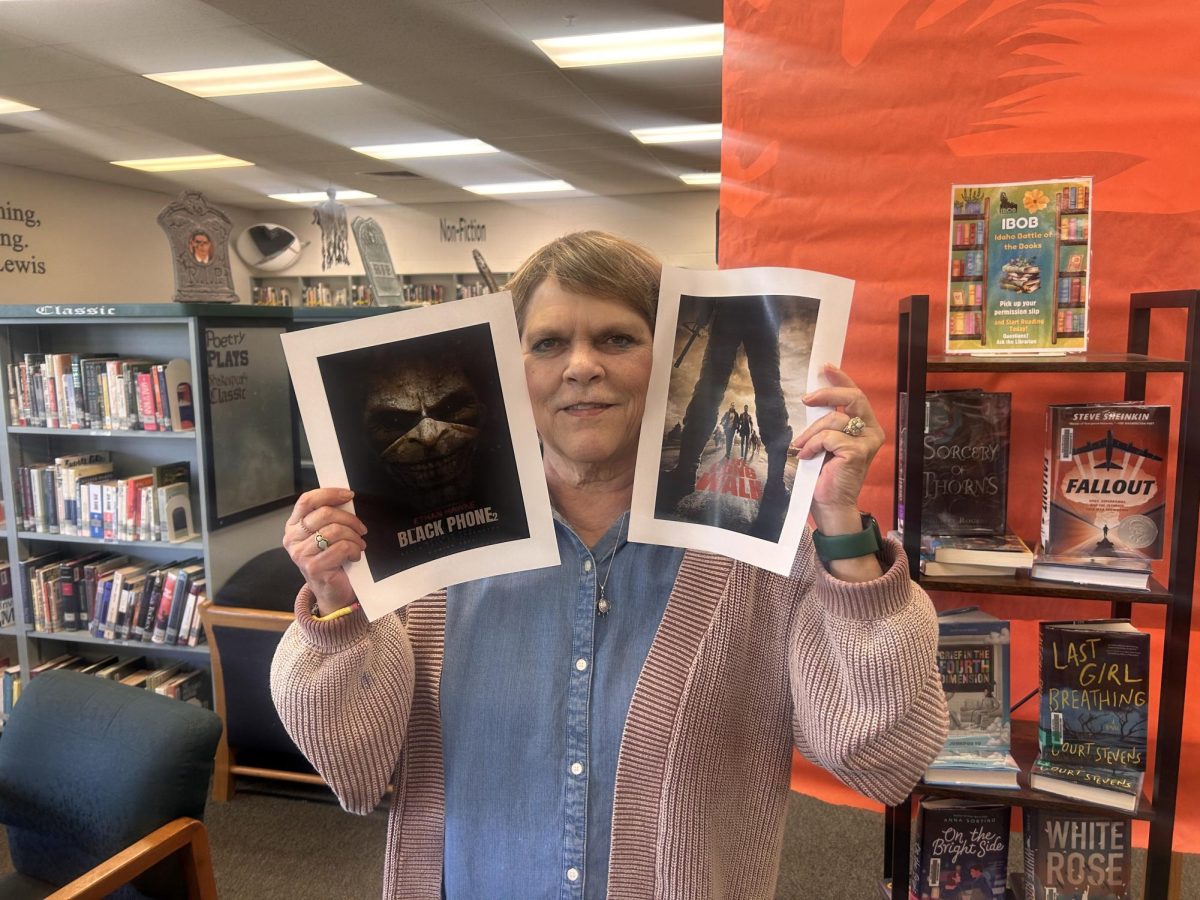

The Black Dahlia case is one of the most infamous cold cases in the U.S.’s history.

Disclaimer: Though this article will not cover this case in full detail, some of the details may be disturbing.

Throughout the 1900s, some murder cases were left unsolved and had people riddled with questions about who the killer may be. Is this due to forensics science not being advanced enough, or was it simply the errors made by detectives of the time?

Though these cases were never answered and may never be, they still help to this day improve police work and forensics. First, though, the question of what even constitutes a cold case is incredibly important.

According to houstontx.gov, “A case becomes cold when all probative investigative leads available to the primary investigators are exhausted, and the case remains open and unsolved after a period of three years.”

Now that the question of whether a cold case is considered a cold case has been answered, it is time to dive headfirst into the case of the Black Dahlia.

At 10:00 a.m. on Jan. 15, 1947, a young woman was found dead by a mother and her daughter at Leimert Park, Los Angeles. The young woman whose body was found had been cut through at the waist and was separated in half. There was no blood at the scene, which inevitably led the police to believe that the unknown woman had been killed elsewhere.

Another indication she had either been killed elsewhere or the murderer may have felt remorse would be that the body had been heavily mutilated. Parts of her body around her thighs and chest had been cut. Along with her face having been slashed into the famous Glasgow smile, where the corners of the mouth are cut to the ears. However, still, there was no blood.

Due to the gruesomeness of the mutilation and how precise the cuts had been, the police began interviewing medical students at USC Medical School.

According to FBI.gov, “The ensuing investigation was led by the L.A. Police Department. The FBI was asked to help…The young woman turned out to be a 22-year-old Hollywood hopeful named Elizabeth Short—later dubbed the ‘Black Dahlia’ by the press for her rumored penchant for sheer black clothes and for the Blue Dahlia movie out at that time.”

The young woman Elizabeth Short was an upstart in Southern California who, at the time, was an aspiring actress, though she had been working as a waitress. She initially applied to be a clerk at the U.S. Army Camp Cooke commissary in 1943. This was discovered because her fingerprints had been on file, which also helped to identify her body. The FBI also found her prints in their system seven months after she applied for the job because she had been arrested for underage drinking.

According to novelsuspects.com, “The LAPD identified Elizabeth Short by her fingerprints, and an autopsy was performed on Short’s body on January 16, 1947. Marks on her body suggested the woman had been bound and tortured, and her official cause of death was cerebral hemorrhage and shock.”

Soon, the press got involved in the case and began to brand her as the famous nickname, The Black Dahlia, for her preference for black sheer clothing and dark black hair.

Even though the case had been incredibly famous, the police had a very difficult time solving the murder. They interviewed hundreds of men that Short knew, but it all led nowhere.

Eventually, on Jan. 24, 1947, “The Los Angeles Examiner” received a letter claiming that the person writing was the one who killed Short. Then, in the letter, they claimed they would send them a package with Short’s personal belongings.

According to localhistories.org, “It contained Elizabeth Short’s birth certificate, social security card, photos, a newspaper clipping about Matt Gordon, and an address book belonging not to Elizabeth but to an acquaintance of hers named Mark Hansen.” In the address book a multitude of pages had also been ripped out and inside it said “Here is Dahlia’s Belonging.”

The body, along with the package and letter, had all been soaked in gasoline to remove any potential fingerprints.

Many people during this time also claimed to be the killer, but those letters and packages did not contain any of Short’s belongings or any other clues that could be confirmed. Therefore, all of these things were disregarded as people chasing fame.

Since then, no one has come close to solving the now-named Black Dahlia murder, and as of 2003, the last detective who was alive working the case died. His name was Ralph Asdel, and he was 26 when he worked on the case. With his death and the longevity of this cold case, it is highly unlikely the case will ever be solved.

This article is purely for informational purposes, and the goal is not to use true crime as entertainment.

For more information, visit fbi.gov, localhistories.org, novelsuspects.com, allthatsinteresting.com, and vault.fbi.gov.